“The growing incidences being reported in electronic media are about “software piracy,” the emergence of cloud software is then a government-funded program to control data across PC’s via online sources without the possibility of physical distribution illegal licensing (Chowbe 20).

As with any other government led propaganda or repulsion technique against piracy, illegal conduct across cloud servers, or “mechanism[‘s] on the Net for which a patent is granted, any person using it without a license can be hauled to the courts” (38). Like many of my other sources, this one also recognized the patent improvements made in the cloud, though “one cannot rule out the continued issue of patents which may be classified as ‘Restrictive Business Practices’” (39). This author stresses the point of importance surrounding the cloud, which is the IP, and its very important role as an “intangible thing” with existential “value in the real world as well as in the electronic environment” (40).

Monetary gain in today’s world is commonly sought, so why do a growing number of consumers partake in illegal accessing of copyrighted content, specifically software? Hindering a developer’s will to innovate also means hampering paychecks for developments to be made, but it also “hamper[s] the sustainability of society, since the intellectual class will lose interest in creativity and innovation” (41). India is a wide distributor of popular cloud-based software developments that advertise daily task enhancement properties suited for business and organized lifestyles. This poses the question of how successful regulation will reduce piracy of software and enhance the usability of innovative software. If unequal regulation continues across the states, it is not whether cloud technology will expand and take on true existential meaning of its own in consumer society, the issue “depends upon its use with effective regulations that don’t allow permissible “havoc” and “mockery” to demean government led “rules and regulations” (41).

The idea of patenting software is becoming an idea of the past, because with the cloud, advancements in management systems via cloud allow users to utilize resources that are constantly changing—so with more developer recognition of consumer intelligence, a semiotic domain can then withstand the current cloud technology copyright law book. In every country advanced to use the web in norm society, new laws are being enforced not only to improve government control over user data in the public domain, but also to prevent piracy via developers’ wishes by prosecuting users with illegally distributed versions of code by traces of IP and general online activity by government-led trackers.

The state of the internet is in need of a universally governed regulation system for copyright infringement. As I have seen in past resources with government cases and lawsuits involving illegally pirated goods, some states take it to court whereas totalitarian regimes take it personal by physically harming the pirate. A global meeting of the minds in recognized as crucial more than ever in order for the current state of law to keep its “relevance in the electronic medium” (41). Innovation is hindered, though, because of mistrust toward the cloud-innovative idea to convert software to only be accessible through IP, in a storage pace physically located wherever containing towers with information computers that provide the backend to projects you digitally create and access via developer servers.

In Andrew Nieh’s Software Wars: The Patent Menace, he points out that technology exists in a fast-paced realm that developers must always consider. He suggests the limitations of a patented online framework will date any software because it is much too slow: “[C]opyright is an important tool that is used to facilitate the open-source software movement” (Nieh 329). And in the open-source software movement are people like Laurence Lessig, founder of the Creative Commons, and strong social advocate for “internet rights.” Software creators can “generate market share for their programs by providing certain components free of charge”—an important mention since companies like Apple are realizing their “voice” and speaking to the public about strategic plans to better software and devices. Through user input and business

planning, a system such as this is necessary for user to be more comfortable with cloud software. The question of software patents is if they need be as they stand in the legal system or dropped for lack of recognition. There is little to be said about recognized developer pushes toward cloud patents of software, but opposite is true for the inclination of copyrights that uphold developer standards of business conduct and acknowledgement of legal by-laws that allow innovative processes via IP. A new government act must respect the privacy of users cloud data/software along with all the various other online concerns: Confidentiality, data integrity, data theft, data loss, data location, deletion of data, malicious insiders, account or service Hijacking, data segregation, and lastly, the cloud’s own users.

Online piracy is too dynamic a “problem” to correct. Becoming a “premier technology” like Adobe’s Photoshop is possible when access to illegal distribution of software makes up nearly half of a customer database. Universally popular webpages such as Reedit and Wikipedia fight for internet rights when threatened; knowing the majority of their followers will understand and support the banner at the top of the page supporting online freedom.

Although unverifiable, a large portion of amateur media is created with illegal software. This includes video tutorials, marketed design resources, and self-published books. And for Adobe, this means “more references to Photoshop’s prevalence” (Jeh366). Dale Thompson calls this the ‘network effect.’ He is an advocate for piracy that was sued by “Adobe, Microsoft, and Rosetta Stone” for hosting the top grossing software online for free—no purchase necessary. He claims online piracy is actually beneficial to software companies. He says, “…with any software, network effects play a large role in whether it gains the critical mass necessary to become a premier technology” (Jeh366). This is a shared perspective by uploaders of illegal content.

Undoubtedly, Adobe Photoshop is known even by people who don’t have any use for it. Software piracy can be differentiated from benefits to specific people as opposed to specific groups of people, i.e., Adobe Photoshop is applicable to many realms of the marketplace, whereas pirating a movie or video game is an individual’s way to save a few bucks and enjoy media on a modern platform.

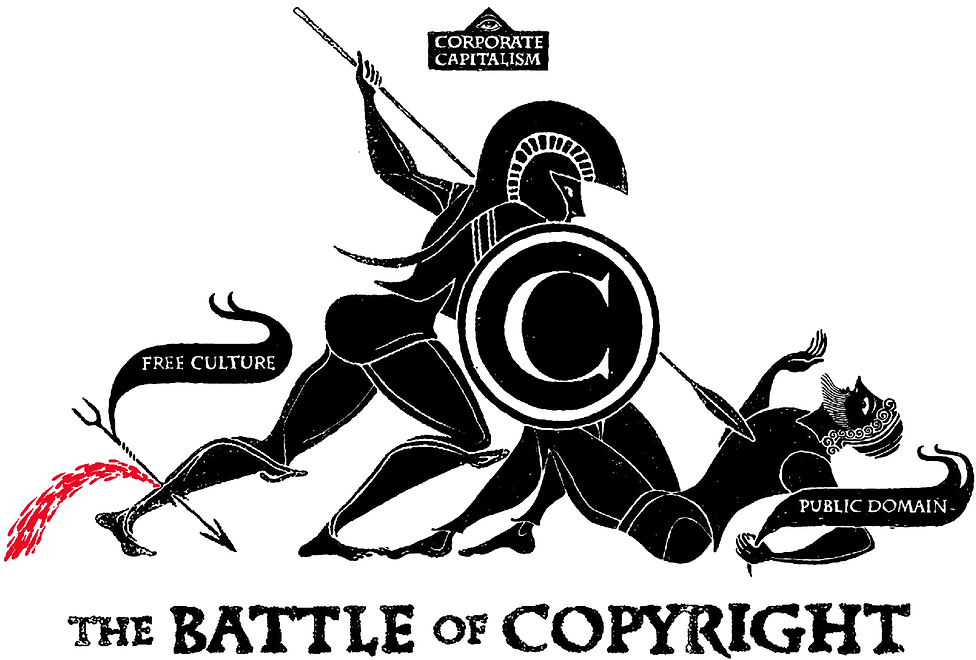

Image by Mike Solita

Online piracy is too dynamic a “problem” to correct. Becoming a “premier technology” like Adobe’s Photoshop is possible when access to illegal distribution of software makes up nearly half of a customer database. Universally popular webpages such as Reedit and Wikipedia fight for internet rights when threatened; knowing the majority of their followers will understand and support the banner at the top of the page supporting online freedom.

Although unverifiable, a large portion of amateur media is created with illegal software. This includes video tutorials, marketed design resources, and self-published books. And for Adobe, this means “more references to Photoshop’s prevalence” (Jeh366). Dale Thompson calls this the ‘network effect.’ He is an advocate for piracy that was sued by “Adobe, Microsoft, and Rosetta Stone” for hosting the top grossing software online for free—no purchase necessary. He claims online piracy is actually beneficial to software companies. He says, “…with any software, network effects play a large role in whether it gains the critical mass necessary to become a premier technology” (Jeh366). This is a shared perspective by uploaders of illegal content.

Video by Digital Skye Media

Undoubtedly, Adobe Photoshop is known even by people who don’t have any use for it. Software piracy can be differentiated from benefits to specific people as opposed to specific groups of people, i.e., Adobe Photoshop is applicable to many realms of the marketplace, whereas pirating a movie or video game is an individual’s way to save a few bucks and enjoy media on a modern platform.

In a short, highly informative article entitled “The Cloud, Not More Regulation, Is Likely Answer to Software Piracy,” the author, John Hayward, states the problem of piracy reached a turning point when the internet became available, “providing incredibly powerful new methods to distribute illicit copies of software.” His primary argument is in the title that developers are switching to cloud, meaning online data storage, in order to combat the huge debt from software piracy. Moreover, in 2013 Adobe released its version of the cloud, with its bundled design software and instant online access to all saved work. This means Adobe's audiences are people with internet access, so will that mean Adobe will be missing potential profit by not reaching out to offline users that prefer an installable copy of their purchase(s).

For software that is only available via a cloud, there is what seems a zero likelihood of piracy, and “at a standpoint of convenience [you have] instant access to purchased software, no need to worry about backups, no lengthy installation process” (Hayward). This article is crucial as it adds to the idea of a cloud takeover while bringing to our attention the issue of this subscription service. When you are no longer a member to the cloud, your data will remain with the software publisher and all you will be left with are copies and redistributed works—no original source files.

Cloud computing is popular, so concerns about privacy and usage success are constantly in question. In an article by Rejoice Paul, he feels it is “necessary to analyze the security issues in cloud computing and make cloud computing more secure and safe.” Software-as-a-service (Saas) diminishes the consumer’s control over the purchase significantly more than using the cloud for Infrastructure-as-a-service (Iaas). Saaas also has the least consumer flexibility, meaning illegal activity is much harder to come across since online servers are likely to detect such activities and prosecute according to government law, even in the instance of offline access. That convenience is gone, but your online information is still subject-to-review by legal professionals.

Much like the evolution of the internet, Rejoice Paul recognized the emerging corporate dependence on the switch to cloud transactions. Through online media reserves, the developer problem of software piracy is at an end—or is it? Because like previously stated, with the development of free market innovation was the steady advancement of development for tools to bypass such innovation. Google knows having a secure database is a fundamental element in online success.

Video by Stewart Room

Cloud computing is popular, so concerns about privacy and usage success are constantly in question. In an article by Rejoice Paul, he feels it is “necessary to analyze the security issues in cloud computing and make cloud computing more secure and safe.” Software-as-a-service (Saas) diminishes the consumer’s control over the purchase significantly more than using the cloud for Infrastructure-as-a-service (Iaas). Saaas also has the least consumer flexibility, meaning illegal activity is much harder to come across since online servers are likely to detect such activities and prosecute according to government law, even in the instance of offline access. That convenience is gone, but your online information is still subject-to-review by legal professionals.

Much like the evolution of the internet, Rejoice Paul recognized the emerging corporate dependence on the switch to cloud transactions. Through online media reserves, the developer problem of software piracy is at an end—or is it? Because like previously stated, with the development of free market innovation was the steady advancement of development for tools to bypass such innovation. Google knows having a secure database is a fundamental element in online success.

We can expect “cloud computing providers [to] regularly back up users’ files and store them on multiple servers, thereby protecting users from losing data when their hardware fails” (Kattan).

There are types of privacy protection available over different modes of cloud application, but consumers should be primarily concerned with RCS servers—servers “the government need only provide notice and establish reasonable relevance to secure a subpoena compelling disclosure.” For ECS servers, privacy protections are more likely to serve the consumer than the governing figure, “[given] the communications have been stored for no more than 180 days” (Kattan). ISP’s do not limit to just one type of server but likely include both RCS and ECS: “[b]y differentiating between storage incidental to transmission and storage for backup purposes, this statement undermines the assumption that storage must be incidental to transmission.” Youtube, “though the court did not explain its reasoning,” provides users with RCS servers. Whereas content posted to sites like Facebook and Myspace constitute ECS servers because the personal information exists on such platforms meant for display and “storage” purposes (Katton). And although this generally the case,

Katton qualifies more secure systems that recognize content from Gmail servers as more than electronic storage, then breaks it down into various complex parts—not to mention complexity of the 180-Day Rule and “Stored Communication Act’s (SCA) current framework.”

Image by Christopher Dombres